Alternative (“alt”) asset managers offer some of the most exciting opportunities for investors. A few of my top picks in this sector saw gains of 5-9% following Election Day. Yet, it’s their long-term potential over the next decade that makes them truly compelling.

On Seeking Alpha, I've published numerous articles on alt managers, whose stocks have delivered impressive returns—my scorecard is here. This post is for those who seek an understanding of how alt managers make money and how investors can benefit. We will often publish about alt managers on Substack.

Most people are familiar with traditional asset managers like Vanguard or BlackRock. They primarily manage stock, bond, and money market mutual funds or ETFs and charge relatively low fees. For some index funds, fees are as low as a few hundredths of a percent, typically staying well within 1%. Both mutual funds and ETFs are highly liquid, allowing investors to buy and sell almost anytime.

Alt managers operate differently. The term "alternative" reflects that the assets they manage are distinct from conventional public stocks, bonds, and cash instruments. The largest publicly traded alt managers include Blackstone (BX), KKR (KKR), Brookfield (BN and BAM), Apollo (APO), Ares (ARES), Carlyle (CG), and Blue Owl (OWL)—seven companies represented by eight stocks, which we’ll refer to as the Big Seven.

KKR was the first industry player followed by Blackstone, Carlyle, and Apollo at the end of the previous century. More than 100 years old Brookfield entered the alt management in a decade. Blue Owl and Ares joined still later. The number of smaller public asset managers is also growing, with new entrants going public at a rate of about one per year.

The best-known alternative asset is private equity, which involves owning non-public companies. Occasionally, an alt manager acquires a public company to take it private, enhances its operations or profitability, and then sells it years later— through an IPO or to another buyer—at a higher valuation, thereby earning a profit. Most alt managers began with private equity, and the industry is sometimes still referred to by this name. However, this term is now limiting, as alt managers have significantly broadened their scope, with private equity now representing only one segment.

Another familiar category of alternative assets is real estate. Firms like Blackstone and Brookfield manage vast, non-public real estate portfolios, spanning a wide range of property types—from storage facilities to data centers to skyscrapers in key cities.

A third type of alternative asset is private credit. While banks hold private loans on their balance sheets, "private credit" generally refers to loans issued by non-bank entities. Since the 2008 Financial Crisis, banks have faced increased regulations, limiting their lending scope. Alt managers seized this opportunity to expand in lending, often targeting riskier loans and underserved markets, including distressed and high-yield debt, whether public or private. Apollo leads in investment-grade private loans, while Ares and Blue Owl focus on below-investment-grade lending.

Two prominent alternative assets today are infrastructure and renewables, which involve building and operating data centers, cell towers, solar and wind farms, toll roads, ports, pipelines, airports, and more. Blackstone and Brookfield are leaders in these areas.

Other alternative assets include venture capital, hedge funds, and cryptocurrencies, though these play a lesser role for the Big Seven (except Blackstone, where hedge funds constitute a distinct segment).

By definition, alternative assets are not traded on public markets and are relatively illiquid. Transforming a piece of real estate or turning around a private company can take years, demanding patient capital due to the long-term, illiquid nature of these investments.

Capital Sourcing

Alt managers can acquire assets by either using their balance sheets and/or raising capital from third parties. The ability to attract extraordinary amounts of long-term capital in all shapes and forms uniquely differentiates the industry.

Some alt managers use very little of their own capital and are considered asset-light, while others are asset-heavy, often committing 15-25% of their capital to investments. This practice, called alignment of interests, demonstrates a shared stake between the alt manager and third parties.

Alignment of interests can help attract third-party capital, but surprisingly, it’s not always essential. Blackstone, the industry’s largest player, is asset-light, contributing only about 0.5% of its assets under management (AUM). Instead, Blackstone’s strong track record, especially in real estate, has proven to be a valuable intangible asset, often outweighing the need for significant capital alignment.

An interesting approach was taken by Brookfield. Their main company - Brookfield Corporation (BN) is asset-heavy and contributes capital to many investments. However, they have spun off a quarter of its asset-light manager which trades publicly as BAM (the balance is held by BN).

Since alt managers require patient capital, institutions with long-term investment horizons, like pension plans, endowments, and sovereign wealth funds, were among the first clients though it started changing recently.

Today, the majority of AUM still comes from these institutions. Institutional capital is committed to large private funds—typically in the billions—which close to new investors once the target amount is raised. This capital remains locked in until the fund’s term ends, usually 5-7 years or more, at which point the principal and profits are returned to investors.

Legally, these private funds are structured as limited partnerships, with the alt manager as the general partner (GP), controlling all operations, and the clients as limited partners (LPs), contributing the majority of capital. GPs typically contribute around 2% of the fund’s capital, while asset-heavy managers like Brookfield or Apollo may invest additional capital as LPs alongside their GP role.

After fully investing a fund’s capital, alt managers often begin raising capital for a new fund with the same strategy. The term "strategy" is key: alt managers manage multiple strategies simultaneously, such as private equity, real estate, and more. These strategies are further refined to meet clients' profiles. In real estate, for example, opportunistic funds target higher returns (20% annually) but carry more risk, while core or core-plus funds focus on safer returns around 7-8%.

Alt managers manage numerous funds across various strategies and vintages. To handle global fundraising, they maintain dedicated sales teams that approach clients directly or through intermediaries. These sales teams, often separate from investment teams, play a critical role in alt managers’ success.

Clients pay close attention to an alt manager’s track record. For example, a large pension fund might initially allocate a small portion to a specific strategy. If this investment succeeds, the fund may entrust the alt manager with more capital across multiple strategies. Today, each of the Big Seven has hundreds of institutional clients globally, many investing across various strategies.

While institutional clients have historically been the primary capital source for alt managers, the latter now approach individuals, including retirees, and insurers as well.

Individual investors can gain exposure to alt managers through their public subsidiaries. For instance, Brookfield offers Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP), Brookfield Renewable Partners (BEP), and Brookfield Business Partners (BBU). These entities channel capital to Brookfield’s private funds, allowing retail investors to indirectly become LPs in multiple funds. Public subsidiaries provide liquidity since investors can buy or sell shares at any time, though this liquidity introduces volatility. Nearly all of the Big Seven have similar publicly traded vehicles focused primarily on debt and real estate.

Increasingly, some wealthier individuals are willing to sacrifice liquidity for potentially higher returns. Previously, this wasn’t feasible through alt managers, but this is changing. Blackstone pioneered this shift by introducing non-traded real estate investment trusts (REITs) and credit vehicles for individuals through independent channels (banks, broker-dealers, registered investment advisors, etc.). Blue Owl followed suit, and others are replicating this strategy. These vehicles allow investors to redeem a limited portion of assets (typically up to 5% per quarter), offering perceived liquidity under normal conditions. However, during financial stress, when redemptions surge, these vehicles may quickly become illiquid, as happened a couple of years ago with Blackstone’s non-traded funds.

Working with affiliated insurers has become a major trend among alt managers, inspired largely by Apollo’s success. The concept is straightforward: certain life insurance products, like fixed annuities, have long-term payout horizons, allowing insurers to hold funds for years. This makes annuities ideal for funding private credit, and it’s a model that has proven highly effective for both Apollo and KKR. Both of them as well as Brookfield house gigantic life insurance subsidiaries.

Independent insurers, both life and P&C, increasingly rely on alternative asset managers to achieve superior returns, primarily through private credit investments.

Fees

Without much exaggeration, alternative asset managers are all about fees. For asset-light managers, various fees dwarf other income sources. Asset-heavy managers also benefit from returns on their own capital but still rely on fees as the most consistent and valuable part of their business. For example, even asset-heavy Brookfield depends primarily on fee income. Apollo (and KKR to a lesser degree), however, stands out due to its insurance arm, Athene, which generates reliable and growing income.

Alt managers are highly creative in structuring fees, but they generally fall into three broad categories: management fees based on AUM (similar to mutual funds), one-time transaction fees for specific deals, and performance fees, which are tied to meeting or exceeding set performance targets within funds. Except for Apollo, transaction fees are relatively minor and often grouped with management fees.

Management fees, which typically start around 1% of AUM (though closer to 0.25% for some credit strategies), are charged quarterly. Given the illiquid and long-term nature of private funds—some of which are even permanent—management fees are continuous, recurring, and predictable.

Performance fees, on the other hand, are more variable. Some are assessed periodically but may be zero if performance targets aren’t met. Others, like carried interest, represent a share of investment gains that alt managers only receive upon a fund’s exit, provided returns exceed a certain hurdle rate.

While performance fees are lumpy and not guaranteed, they can be substantial. For some managers, like Blackstone and Carlyle, performance fees are close in importance to management fees. Others, like Ares and Blue Owl, are management fee-centric.

An essential point is that performance fees are closely aligned with market cycles—when markets perform well, so do these fees. Management fees, in contrast, are generally unaffected by market fluctuations, providing steady revenue in both good and challenging times.

Asset under management

AUM is the single most important metric for all asset managers as it is directly related to the size of fees. Unless you believe that alternative AUM will grow at a high rate, there is no reason to invest in alt managers. The inverse statement is also true: as long as alternative AUM grows fast, there is little risk of losing money investing in the Big Seven.

The AUM growth is controlled by both supply and demand. Supply denotes assets that could be turned private provided funding is available. The total amount of alternative AUM today is estimated at ~$13-15T with ~40% of it in private equity. This figure should be compared with the global public equity market cap of ~$95T and the global bond market of ~$ 100+T.

But this is not all. A lot of new private assets will be needed to fund infrastructure, renewables, retirement, etc. On the slide from Apollo below, you can see an estimate of private assets that may be needed for these purposes.

The Big Seven are expected to benefit disproportionately from this growth. First, an alt manager needs a big network of offices and professionals to select the most promising opportunities from the abundance. And secondly, big transactions (which are often the most lucrative) are simply out of reach for smaller players. For example, recently Brookfield (and later and separately Apollo) joined forces with Intel (INTC) to provide $30B for building a chip plant in Arizona on a fifty-fifty basis. How many companies in the world can quickly accomplish due diligence and commit to a check for $15B?

Let us turn our attention to demand now. It exists because alt managers deliver higher returns for their clients AFTER FEES. While it does not happen always, it is generally the case. Otherwise, sophisticated clients, like insurers, pensions, or endowment funds, would not be increasing their allocations to alts.

When we talk about investment companies, Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A, BRK.B) is always the first to come to mind. But how many people are managing investments at Berkshire? Just a handful. A big alt manager employs hundreds of investment professionals spread around the world who are sifting through hundreds of investment opportunities in different industries, geographies, and asset classes. Only a small fraction of opportunities is selected for investments and leverage is applied to those few chosen.

Since investment professionals within the Big Seven are paid extremely well, investment talent is flocking there. It is similar to how Google attracts programming talent. Blackstone reported that for the analyst class position in 2018, only 86 were hired out of 14,906 applicants. The scale and quality of investment talent represent the second major intangible asset of big alt managers.

The crucial figure is the AUM growth rate that alt managers have achieved. So far, it is close to 20% for most of the Big Seven! They project similar rates of growth in the foreseeable future.

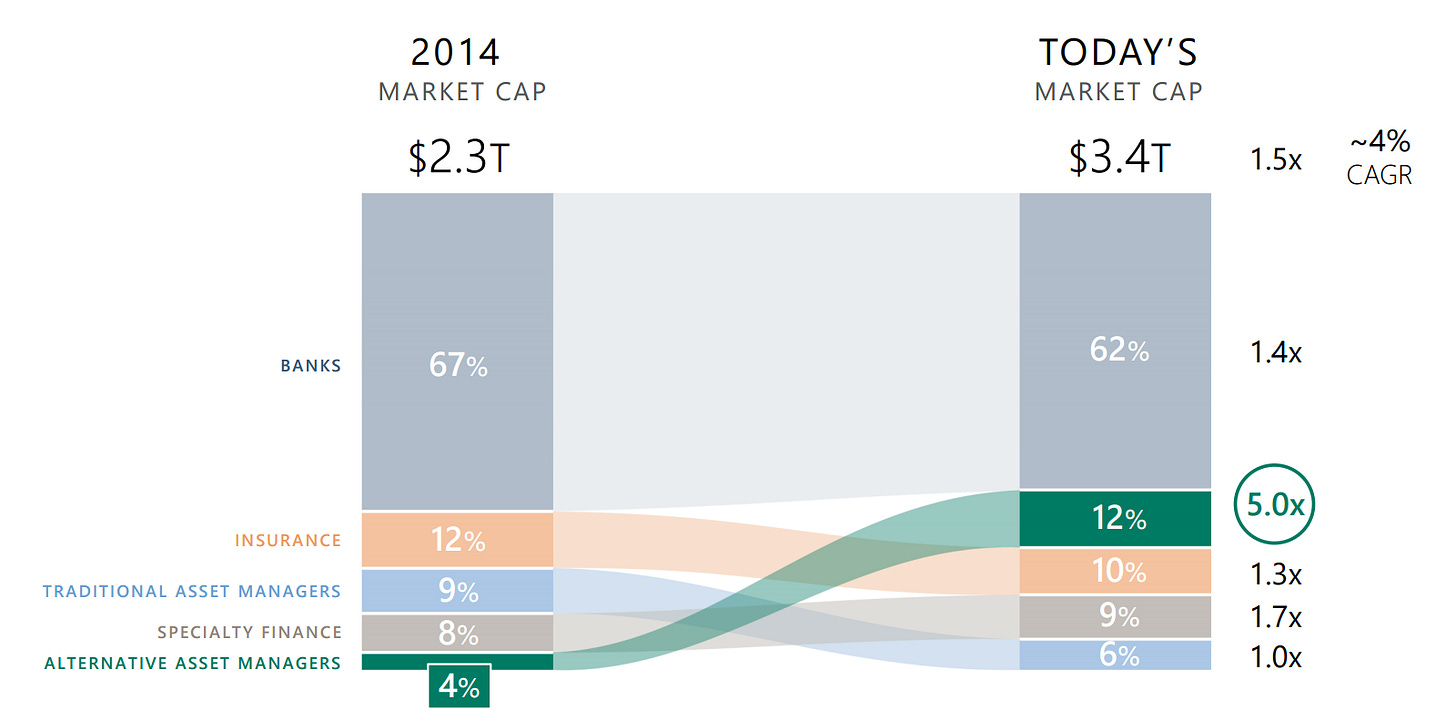

This growth quickly changes the role of alt managers in the economy. Below is another slide from the recent Apollo Investor Day that illustrates it.

In 2014, alt managers constituted 4% of $2.3T of financial services capitalization. Today it is 12% of a $3.4T pie. It means 5.0x grows in absolute figures!

Controversies and risks

Many view alternative asset managers as ruthless, overleveraged players who keep their accounting opaque and inflate returns on private funds. This reputation primarily stems from private equity operations, particularly leveraged buyouts. The phrase “Barbarians at the Gate”—a reference to one of KKR's notorious buyouts—remains firmly associated with private equity’s image.

However, private equity is now just one segment of the broader alt-management business. Segments like private debt, infrastructure, retirement solutions, and renewables lack this negative connotation.

But what about leverage? Are alternative asset managers truly that leveraged and risky? While they indeed use substantial leverage, it is typically non-recourse for the managers themselves. The parent companies carry minimal or no debt, isolating them from the risks of leveraged investments within their funds.

Let’s address another misconception: the complexity of their financial statements. Indeed, GAAP (or IFRS, in Brookfield’s case) financials are challenging to interpret, as alt managers consolidate private funds they control, regardless of their minimal investment in them. With tens of funds under management, each investing in, managing, and eventually selling multiple assets (like companies, properties, or renewables), consolidating these entities creates GAAP statements that are nearly unreadable. To provide clarity, alt managers publish non-GAAP statements that exclude these fund assets, focusing primarily on fee-based income and reconciling back to GAAP. These non-GAAP statements are relatively straightforward, especially for asset-light managers.

Some critics argue that alt managers inflate fund returns to lure “naive” pension plans—a view popularized in the recent book, The Myth of Private Equity. While the book is entertaining, I disagree with this assertion. While some pension plans may be bureaucratic or less sophisticated, many institutional clients, such as endowment funds and insurance companies, are highly knowledgeable investors. Not all pension plans are “naive” either. With nearly 10,000 institutional clients worldwide, including some of the most experienced investors, alt managers cannot achieve such scale without delivering real value.

Now, let’s discuss the real risks. The first is volatility. For example, Apollo’s stock surged by more than 50% between its Q2 and Q3 reports this year without any significant news. This level of volatility is common among alt managers. While the justification for such volatility is debatable, investors should be prepared to navigate it and, where possible, capitalize on it.

The bigger risk, however, is a slowdown in growth rates. Alt managers are typically valued at high multiples due to high expectations. While I don’t foresee a slowdown, it remains a possibility that investors should be mindful of.

Alex - you're coverage on SA has always been great. You're one of my favorite authors to read and you have helped me understand AAMs much better - and it has been quite a financial boon for me. Keep up the good work - I'm excited you have created a page with more frequent postings!

Very clear and interesting explanation. My single largest position in my taxable portfolio is BX; just out of curiosity wonder which of the big 7 are best positioned for the near term?