Magician Apollo Transforms Life Insurance

Insights about Apollo's business model that has tripled its stock price in 3.5 years.

In March 2021, I saw news of alternative asset manager Apollo Global (APO) announcing its merger with life insurer Athene (then a publicly traded company, ATH). The transaction, structured as an exchange of ATH shares into APO, caught me by surprise. At the time, I had been a long-term holder of another alt manager Brookfield (BN, BAM), actively following the industry for years, and frequently publishing about it.

Still, I could not figure out why a nimble Apollo with quickly growing earnings and dividends would merge with a massive and stodgy life insurer. I started reading whatever Apollo/Athene published about this bizarre combination (Apollo and Athene were the only sources!), learned of CEOs Marc Rowan and James Belardi, and after about a week of evaluating the merger bought both APO and ATH (assuming closing, ATH was slightly cheaper). It took a long time for investors to come to terms with this merger and I kept adding to my stake for about a year.

I have published many articles on Seeking Alpha about post-merger Apollo’s business model. So, I feel I owe at least one article to my Substack subscribers.

What follows requires an understanding of the alternative asset management industry aka private equity. If it puts you on shaky ground, please read my “Primer On Alternative Asset Managers” on Substack without a paywall.

Berkshire's business model

Warren Buffett popularized the close connection between insurance and investments. Most of my readers must have read Buffett's annual letters explaining this, but I will repeat his mantra in short.

Insurers receive premiums before paying claims, allowing them to generate "float" - cash reserved for paying future claims that can be invested meanwhile. As long as a property and casualty ("P&C") insurer is growing and generates underwriting profits (i.e. its premiums are greater than the sum of its claims and expenses), its float grows as well. For our ever-profitable and ever-growing insurer, today's float is a liability that will NEVER be paid (because it will only grow) and can be used for long-term investments such as buying stocks or acquiring businesses.

As far as I know, nobody before Buffett formulated this principle so openly. Most of the real-world insurers are less confident in their underwriting profitability and/or their growth and invest their float mostly or only in reliable bonds. And even Buffett rarely ventured outside cash and bonds when investing float.

For Berkshire, insurance always means P&C operation (not counting some life reinsurance). This is not by chance. P&C insurance has short-duration contracts (typically one year and even less for Geico) and at the end of the contract term, a conservative carrier knows its underwriting results fairly well. Thus both underwriting profits and float are available in cash and can be invested, at least partially, in stocks or acquisitions.

On the contrary, contracts for life insurers have a long duration, profits are accounting-driven, and accounting itself is arcane. Actual cash is unambiguously generated only at the end of the long-term contract. This makes life insurance unattractive for a capital allocator like Buffett.

Hedge funds and insurance

Some hedgies tried to exploit insurance differently. For reasons that will become clear shortly, we will spend a couple of paragraphs on it.

The two well-known examples involve famous hedgies, Daniel Loeb and David Einhorn. Both set up affiliated/controlled public reinsurance companies in the Caribbean that paid investment management fees to their hedge funds. As long as one trusts publicly announced plans, these reinsurers were supposed to benefit from the hedgies' investment acumen and offshore taxation.

In reality, hedge funds were the only beneficiaries. Hedgies viewed reinsurers' float as a permanent capital to manage and an endless source of fees. Under this lens, reinsurance underwriting was secondary, and overall performance was mediocre, to put it mildly. Investors in these public reinsurers have not fared well while hedge funds pocketed hundreds of millions in fees.

Athene and Apollo

Apollo co-founded insurer, Athene, right after the Financial Crisis and became its major shareholder. James Belardi, a long-time insurance executive who is still Athene's CEO, was another co-founder. Athene's design was based on insights that Belardi had learned for 20 years of his insurance career.

The timing of Apollo's entry into the insurance industry was not accidental. After the Financial Crisis, banks became tightly regulated and had to limit their lending activities. The need to borrow money, meanwhile, kept growing in line with the economy. This mismatch had created a profitable niche to exploit and Apollo made a decision to become a non-bank lender. Back then, very few, besides Apollo, figured out the long-term consequences of the Dodd-Frank Act and similar regulations.

At that time, Apollo was an asset-light alt manager without the wherewithal to fund any loans. The answer was to lend other people's money, i.e. Athene's float. Apollo was supposed to benefit by charging fees for managing Athene’s investment portfolio consisting mostly of these loans.

While the concept itself was rather novel, its implementation required special skills and imagination. However, James Belardi had done something similar for his previous employer.

Banks fund their loans with customers' deposits. Insurance companies, in principle, can fund loans with underwriting liabilities aka float. But not all floats are created equal. Buffett needs P&C short-duration float to fund equity investments for the reasons I already explained. On the contrary, Apollo needed long-duration liabilities to benefit from the illiquid long-term nature of private credit. Of all insurance companies, life insurers have the longest-duration float and so Athene was destined to become a life insurer.

This solution had another important benefit: a typical assets-to-equity ratio for life insurers is 10:1 or even higher. Since Apollo's fees are based on AUM, it provided a simple way to generate a lot of fees on a rather small equity investment.

The critical step in Athene's design was a strict limitation on products it would underwrite. Oversimplifying a bit, Athene would specialize only in annuities.

The simplest type of annuity is a fixed annuity when a customer gives an insurance company a certain amount of money with an exact knowledge of how much and for how long she will receive back from it at a future date. This type of annuity is quite similar to a long-term bank CD. There are other types of annuities with fixed-indexed annuities being especially popular. Some annuities also include elements of mortality risks. However, by using derivatives, reinsurance, and hedging, a life insurance company can reduce a more complicated annuity to a simple fixed annuity. If it is not possible, Athene is not interested in underwriting the product. Nor it is interested in other insurance products such as P&C, medical insurance, long-term care, variable annuities, and so on.

In this regard, Athene is an insurance company that closely resembles a bank with funding from annuity liabilities in place of customers’ deposits. As long as Athene's return on investments is greater than annuity funding costs plus operating expenses, it generates spread-related earnings ("SRE").

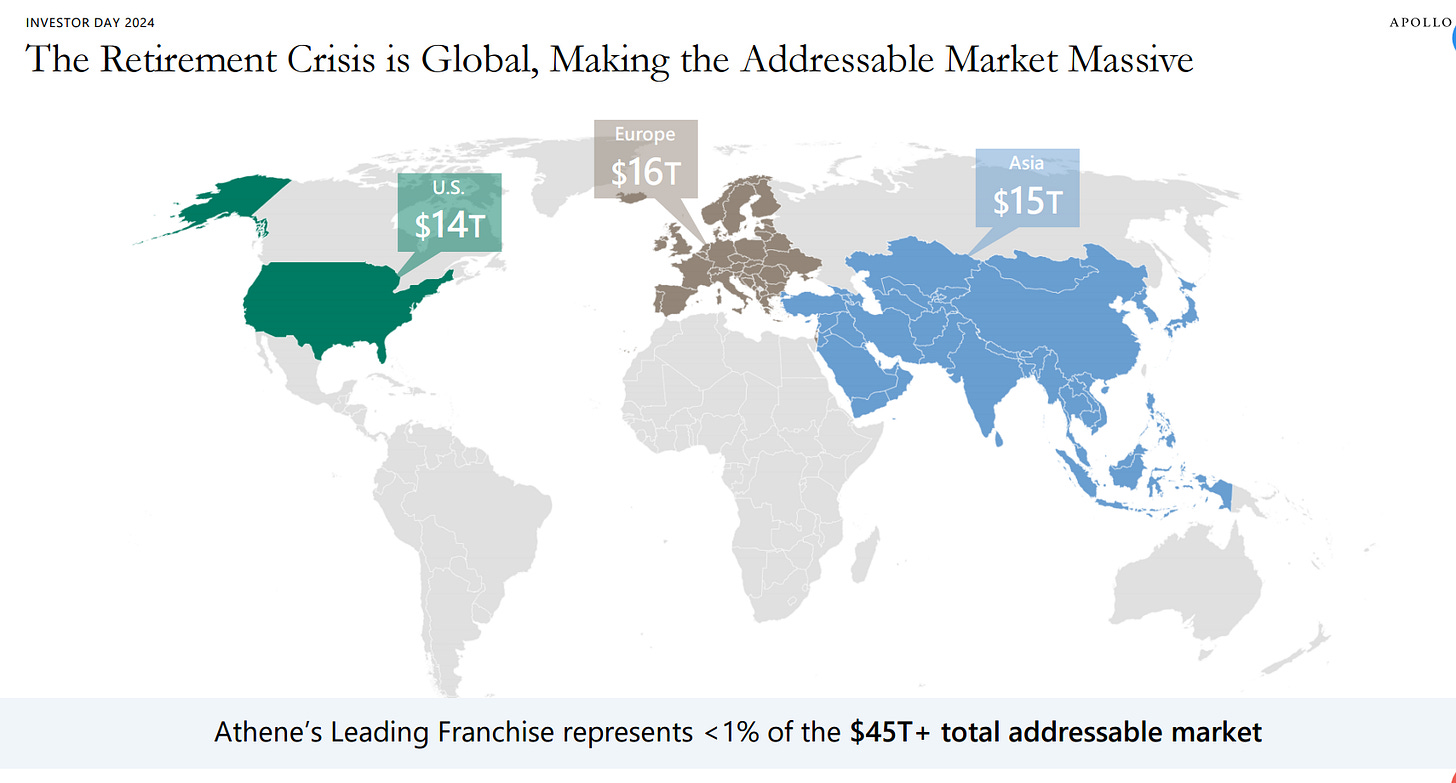

Since annuities are primarily for (future) retirees, Athene has become a specialist retirement company and that is how it positions itself. Due to population aging, retirement funding will remain a growing industry for years to come (“silver tsunami”). That was another insight needed to start Athene. It would be up to retirees to fund Athene’s loans that Apollo would originate and manage!

Athene acquires annuities via several organic channels. First, from individuals through different intermediaries. Secondly, by reinsuring annuity liabilities generated by other insurers. Thirdly, by acquiring closed blocks of already existing annuities from other insurers. Fourthly, by agreeing to provide defined benefit pensions to employees of third parties (it is also called a group annuity or a pension risk transfer). And finally, by agreeing to take deposits from institutions (something like corporate CDs with either fixed or floating rates) - the so-called funding agreements that are not related to annuities but are similar in structure.

While much of the above might seem obvious today, it was far from evident back in 2008–2009. It appeared particularly unconventional for a high-flying private equity firm to dive into the slow-paced, conservative world of life insurance. Furthermore, the fees Apollo could expect to earn from managing $1 of debt were significantly lower than those from managing $1 of equity. Yet, Marc Rowan, one of Apollo's three co-founders, emerged as a champion of the insurance strategy.

There is undeniable proof of how inventive Apollo’s insurance strategy was. It would take many years for competitors to clone it.

Despite all the efforts in design and successful implementation, Athene as a public company had never traded well. Many investors (including truly yours) considered Athene a means to create AUM for Apollo's fees and nothing else. It is a natural conclusion once one is familiar with hedgies' insurance experiments.

The Apollo-Athene merger announcement caught me completely by surprise. Since Apollo was already managing Athene’s investment portfolio, the merger wouldn’t generate additional management fees. To understand Apollo’s motivation, I began examining Athene with fresh eyes. Through the lens of the merger, it became clear that Athene could be far more than just a source of AUM for Apollo.

One of Apollo's tenets is that "purchase price matters". This was the case with Athene because it was trading poorly. The purchase was done by issuing additional shares of Apollo at around P/E~6. Estimates show that today Athene is valued at a P/E of about 12-15.

The low price of the merger was a prerequisite, not the motivation. The true driver was achieving full alignment of interests between the two sides. For Athene, it was beneficial as Apollo would now focus on both Apollo’s FRE and Athene’s SRE. Less apparent was how Apollo itself would gain from Athene’s capital generation. Pre-merger, Apollo, as an asset-light firm, distributed nearly all its earnings as dividends to shareholders. In contrast, Athene generated surplus capital beyond its growth needs, which could be paid out as internal dividends to Apollo. These dividends, along with the resources of Athene's vast balance sheet, allowed Apollo to fund long-term investment opportunities that were beyond the scope of the asset-light firm.

The world according to yield

There are three components of Athene’s success:

Liabilities consist of nothing but fixed annuities or financially similar products. This narrow product set is viable because of the strong demand for retirement products from the aging population.

The lowest operating costs in the industry. This is possible due to the same narrow product focus combined with scale. Athene has become number one in fixed annuities in the US.

Outperformance of Apollo-managed assets AFTER APOLLO’s FEES.

This overperformance seems small at only 0.3=0.4% but Athene's assets are ~11-12 times higher than its equity and it allows it to generate ROE several points higher than its competitors!

Since Apollo charges Athene approximately 0.25% of its investment portfolio in fees (excluding certain additional fees in specific cases), Athene's investment portfolio must deliver returns—before management fees—that are 0.6–0.7% higher than what traditional methods can offer. For fixed-income investments, returns closely correlate with yield, making Athene a yield-driven powerhouse. Crucially for an insurer, this yield outperformance must be achieved without compromising credit quality!

Normally, life insurers’ portfolios consist of investment-grade bonds, some safe loans such as high-grade mortgages, and a limited exposure to equities. Let us take a look at Athene’s balance sheet (the slide is several quarters old but the balance sheet structure has not changed).

There are two components of "secret sauce". First, part of Athene's equity (but not float!) is invested in various equity-like alts across Apollo's strategies. They generate annual returns of about 11% on average after Apollo’s fees with lower volatility compared to equities.

The rest of the portfolio is in fixed income. Less than a half of it is in corporate and government bonds not different from other life insurers. But the other half consists of investment-grade securities originated mostly by Apollo itself.

To originate debt, Apollo has 15-16 internal independent underwriting groups that specialize in lending to a vertical the group knows in detail (all of them are on Athene’s balance sheet!). For example, one group may specialize in senior secured lending to mid-market companies, another in commercial mortgages, still another in aircraft leasing, and so on. Apollo is always on the prowl to start, hire, or acquire new groups in different geographies to cover more and more lending niches. These groups are successfully competing against banks and surprisingly often cooperate with them. Per Apollo's estimate, only about 20% of US lending today is originated by banks. To make our discussion more down-to-earth, I will bring a simple business case that I was involved in.

My friend was selling his medical office in New York which he did not need anymore. The property had certain issues but eventually, he found a buyer who agreed to buy it. The buyer wanted to start a cosmetics business in the office but she was a newcomer to the US and did not have a credit history needed for a mortgage. However, she offered to pay my friend 2/3 of the purchase price in cash plus a 5-year seller-financed interest-only mortgage with a balloon payment at the end. My friend did not need cash and was agreeable to this structure.

Upon closing, my friend would originate a mortgage that banks did not want. To me, this mortgage seemed rather safe because of the claim seniority, collateral quality, and low loan-to-value ratio. In my friend's portfolio, this loan could become a bond replacement, paying a higher yield without higher risks at the cost of illiquidity. In the worst-case scenario, my friend would have to foreclose on the property.

I recently tried to arrange a similar deal selling one of my properties. Had it worked, I would have gotten a mortgage to replace bonds in my portfolio. However, this mortgage would yield more than bonds without higher risks.

Apollo's underwriting groups differ from these simple cases because of the scale, flow, and securitization. Apollo's groups can set up a flow of sizable deals in different verticals and then securitize them making the end product investment grade with a higher yield (I am hopeful my readers are familiar with securitization - it will take me too long to explain it here). Similar to my friend's case, the underlying loans are rather illiquid but that is acceptable for entities with high-duration liabilities like Athene.

Several conditions are important for this type of activity: the claims should be senior; the loans are often tailor-made rather than standard; documentation control is essential for downside protection and favorable covenants; and the loans should be funded rather quickly to make it convenient for the borrower.

Before the Apollo-Athene venture, private credit implied primarily either distressed debt or junior speculative debt. Working with Athene, Apollo has become a specialist in high-grade debt, initially unique among alt managers. The ability to generate investment-grade debt (though illiquid in most cases) has led to two important consequences. First, Apollo's high-grade products are fit not only for Athene but also for other insurance companies, pension funds, and certain other types of investors. Secondly, Apollo has become capable of offering holistic and complicated capital solutions to big companies across the credit spectrum - from equity to investment-grade debt to speculative debt with everything in between. Some of these deals have already been spectacularly successful like financing and makeover of Hertz, for example.

Apollo defines its objective in private credit as delivering better returns per unit of risk. Risk in this case is measurable as either back-looking historical credit losses (Athene's credit losses are very low, lower than those of its peers in life insurance) or forward-looking debt metrics. As long as Apollo-originated products are attractive in this regard, they end up on either Athene's balance sheet (generating both FRE and SRE), in Apollo's private funds (generating FRE), or on third-party balance sheets (generating transactional and sometimes, management fees as well).

Risks and attractions of Apollo's model

Athene has benefited handsomely from the model because of the higher return its portfolio generates. To illustrate it I will copy some slides from Apollo-Athene presentations without further comments.

Athene’s growth has quickly and ORGANICALLY increased Apollo’s AUM and FRE. It has also expanded Apollo’s addressable market since the alt manager can now deal with all kinds of debt, and the demand for higher-yielding investment-grade debt should land new clients and additional fees.

It does not necessarily require having an insurer on the alt manager's balance sheet. Apollo has leveraged Athene by attracting third-party capital, in various forms, that can invest along Athene or into the same products. It generates additional fees for Apollo. With time, other alt managers have implemented Apollo-Athene’s model. Some (KKR, BN) cloned it, and others (Blackstone, Blue Owl) did it in the asset-light form.

There are two main risks in the model. First, Apollo-generated investment-grade assets are relatively new compared with well-known traditional bonds. This risk, however, is less than it seems as Apollo-originated loans are not different from bank loans that everybody is familiar with.

So far, Athene's credit losses have been lower than those of its peers. Athene regularly stress-tests its portfolio trying to simulate the environment of the Financial Crisis or even worse and publishes the results on its website. Nothing portends any trouble.

The second risk is mass surrenders, common to all life insurers. It is a rather rare event that has not happened in the US for many years. The last mass surrender I know happened in South Korea in the nineties when the country’s life insurance system was fairly young and immature. Most of Athene’s policies are either non-surrendable or protected by high surrender fees. The company also maintains high liquidity as an additional safety measure.

But still, the only way to avoid the insurance risk is to keep the insurer separate from the alt manager. This is the reason why Blackstone and Blue Owl are staying asset-light.

Conclusion

Apollo and Athene came up with a new way to combine investments and insurance. This model is gradually becoming as enviable as Berkshire's. Since merging with Athene, Apollo’s stock has generated amazing returns to make many interested.

Other big alt managers are developing and fine-tuning their recipes to combine insurance and investments following Apollo's blueprints. Some life insurers are trying to exploit Apollo-Athene’s model from the insurance side by either signing agreements with alt managers (F&G Annuities and Life, for example) or by developing in-house asset origination expertise (Legal & General).

We may see further investment opportunities related to this new model.

Good work, thanks! APO was added to the SP500.

All I know is - I am extremely grateful you opened my eyes to this stock 2 years ago, lol. Now it's going into the S&P - wonder if it gets permanently rerated upwards after years of trading at a lower valuation. I mean look at what happened with KKR.